According

to James, “I take Kanhai as the high peak

of West Indian cricketing development. West Indian cricketing had reached

such a stage, that a fine cricketer could be adventuresome, and Kanhai

was adventuresome…People felt that it was more than a mere description

of how he batted; it was something characteristic of us as cricketers.

They felt that it was not only a cricketing question, because Kanhai was

an East Indian, and East Indians were still somewhat looked down upon

by other people in the Caribbean. But I stated that here was a cricketer

who was doing things that nobody else was doing, and I was very pleased

when he became the captain of the West Indies side.”

A great West Indies cricketer in

his play should embody some essence of that crowded vagueness which passes for

the history of the West Indies. If, like Kanhai, he is one of the most remarkable

and individual of contemporary batsmen, then that should not make him less but

more West Indian. You see what you are looking for, and in Kanhai’s batting what

I have found is a unique pointer of the West Indian quest for identity, for ways

of expressing our potential bursting at every seam. So now I hope we understand

each other. Eyes on the ball.

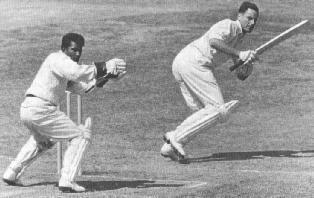

The first historical innings (I prefer to call them historical now) by Kanhai was less than 50, for British Guiana against the Australians of 1956. Kanhai had nor yet made the West Indies team. He played well but what was remarkable about the innings was not only its promise but that he was the junior in a partnership with Clyde Walcott as senior.

Yet the innings in 1957 that future

events caused me to remember most strongly was his last ten innings at

the Oval. He faced Trueman and immediately hit him for two uninhabited

fours. Gone was the restrain that held him prisoner during all of the

previous innings against England.

In Australia, Frank Worrell made

West Indians and the world aware of what West Indians were capable of when their

talents had full play. That is Worrell’s gift to the West Indian personality…Knahai

continued to play that way all through the season. When he made a century in each

innings against Australia, he was within an ace of making the second century in

even time. Hunte being run out in an effort to help Kanhai towards the century,

Kanhai was so upset that it was long minutes before he could make the necessary

runs.

Kanhai continued to score, in the

West Indies, in India, in Pakistan, but the next great landmark of his career

was his innings against England at the Oval in 1963…at the Oval, with the fat

of the match depending to a substantial degree on his batting (Sobers ran himself

out) in this his last test Innings in England, Kanhai set off to do to the English

what he had done to the Australians.

1964 was a great year…all through

1964 I sat in press boxes, most often between Sir Learie Constantine and

Sir Frank Worrell. We were reporting England against Australia; there

was a lot of talking about cricket and naturally about awest Indian cricketers.

About Kanhai, for quite a while the only thing notable said was by Worrell.

He made a comparison between Kanhai and Everton Weekes as batsmen who

would stand back and lash the length ball away on the off-side or to the

on-boundary. Then at Leeds, Kanhai himself turned up and came and sat

in the press box. Learie had a long look at him and then turned to me

and said, “There is Kanhai.

You know at times he goes crazy.”

I knew that Learie had something

in mind.I waited and before long I learnt what it was. I shall try as

far as I can to put it in his own words. “Some

batsmen play brilliantly sometimes and at ordinary times they go ahead

as usual. That one," nodding at Kanhai,

“ is different from all of them. On certain days, before he goes into

the wicket, he makes up his mind to let them have it. And once he is that

way nothing on earth can stop him. Some of his colleagues in the pavilion

who have played with him for years have seen strokes that they have never

seen before: from him or anybody else. He carries on that way for 60 or

70 or 100 and then he comes back with a great innings behind him.”

At Scarborough, Kanhai

was testing out something new. Anyone could see that he was trying to sweep anything near the leg

stump round to fine-leg to beat both deep square and long-leg. He missed

the ball more than he connected. That was easy enough. But I distinctly

remember being vaguely aware that he was feeling his way to something.

I attributed it to the fact that he was playing league cricket all season

and this was his first first-class match. Afterwards, I was to recall

his careful defense of immaculate length balls from Trevor Bailey, and,

without any warning or fuss, not even a notable follow-through, he took

on the rise and lifted it ten feet over mid-on’s head to beat wide long-on

to the boundary; he never budged from his crease, he barely swung at the

ball. Yet, as far as he was concerned, it was four predestined.

We went to Edgbaston. Bailey’s side had six bowlers who had bowled for England that season. If the wicket was not unresponsive to spin, and the atmosphere not unresponsive to swing, the rise of the ball from the pitch was fairly regular. Kanhai began by giving notice that he expected test bowlers to bowl at length; balls a trifle loose so rapidly and unerringly paid the full penalty that by the time he had made 30 or 40 everyone was on his best behaviour.

Kanhai did not go crazy.

Exactly the reverse. He discovered, created a new dimension in batting. The only name I can give to it is “cat-and-mouse.” The bowler

would bowl a length ball. Kanhai would play a defensive stroke, preferably

off the front foot, pushing the ball for one, quite often for two on the

on-side—a most difficult stroke on an uncertain pitch, demanding precious

footwork and clockwork timing. The bowler, after seeing his best lengths,

exploited in this manner, would shift, whereupon he was unfailingly dispatched

to the boundary. After a time it began to look as if the whole sequence

had been pre-arranged for the benefit of the spectators. Kanhai did not

confine himself too rigidly to this pre-established harmony.

One bowler, to escape the remorseless

billiard-like pushes, brought the ball untimely up. Kanhai hit him for six to

the long-on off the front foot. The bowler shortened a bit. Kanhai in the same

over hit him for six in the same place, off the back foot this time. Dexter, who

made a brilliant, in fact, dazzling century in the traditional style, hit a ball

out of the ground over the wide mid-on. Kanhai hit one out of the ground some

40 yards further on that Dexter. He made over 170 in about three hours.

They were wrong. Kanhai

had found his way into regions Bradman never knew. It was not only the

technical skill and strategic generalship that made the innings the most

noteworthy I have seen. There was more to it, to be seen as well as felt.

Bradman was a ruthless executioner of bowlers. All through this demanding

innings Kanhai grinned with a grin that could be seen a mile away.

Cricket is an art, a means of national expression. Voltaire says that no one is so boring as the man who insists on saying everything. I have said enough…But I believe I owe it to the many who did not see the Edgbaston innings to say what I thought it showed of the directions that, once freed, the West Indian might take. The West Indian in my view embody more sharply than elsewhere Nietzsche’s conflict between the ebullience of Dionysius and the discipline of Apollo. Kanhai’s going crazy might seem to be Dionysius in us breaking loose…maybe I saw only what I was looking for. Maybe.

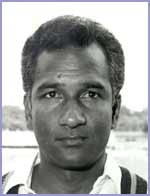

Rohan

Babulal Kanhai

Known

as: Rohan Kanhai

Born:December 26, 1935

Test Career: 1957 - 1973/74,

79 Tests

F/C Career: 1954/55 - 1981/82, 416 matches

Style: RHBat, RAMedPace,

WK

Profile:

Rohan Kanhai's debut for West Indies in 1957 was as an opening batsman

(and wicket keeper!). However, in the following year, on Everton Weekes' retirement,

he settled comfortably into the number three spot. In the 3rd Test against India

he made his maiden century, going on to score 256, at that time the highest test

score ever recorded in India. He had an exhilarating style and for a short time

was Captain of the West Indies.

Test Statistics:

Inns NO Runs

HS Avg 100s 50s Ct

St

137

6 6227 256

47.53 15 28 50 -

F/C

Statistics: Inns NO Runs

HS Avg 100s 50s

Ct St

669

82 28774 256 49.01

83 318 7