| by Rakesh Rampertab |

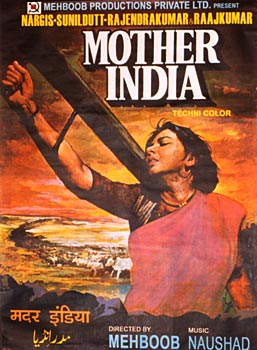

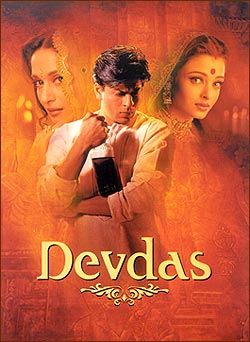

Mr. Frederick Kissoon is right to lament the prejudices of Bollywood films (Chronicle 5/31). But I disagree that Hindi films ought to be banned. Ban is more than a word. It is the way of an Ayatollah and makes censorship of art tyranny. Banning may destroy the art form, but not the content, prejudice. The Taliban destroyed beautiful, enigmatic statues of the enlightened one, but not Buddhism. While the practice of prejudice is undemocratic, its portrayal is not. Despite its flaws, the Hindi film is too important to be abandoned. At its best it is serious art; from “Mother India” to “Sholay” to “Lagaan” (2003 Oscar nomination), it is a staple in world cinema and prominent film festivals (e.g., the 2003 Cannes [France] festival, where Ms. Aishwarya Rai was a judge and a few of Mr. Bachhan’s movies played.) Last year, while Bachhan was voted the most influential actor of all time (BBC world survey), ahead of Mr. Charles Chaplin, etc., the New York Film Forum did a series on Ms. Shabana Azmi. Mr. Raj Kapoor, in his days, was a household name in old Russia, and in numerous African nations today, Hindi film is adored as in Guyana. It is reasonable, therefore, to conclude that the Hindi film has redeeming values.

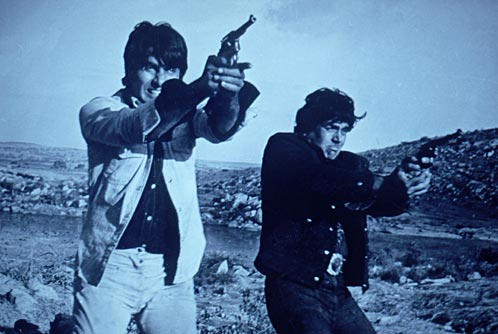

Sholay starring Amitabh and Dharmendra. linked to Indian folklore and pastoral life. To dismiss Hindi film is to dismiss the dance. For us all, Indian or not, the dance is too personal and primordial to be tampered with. It is easy to misunderstand or mock Indian movies, without knowledge of its sophisticated nature. Some brief points; like modern Indian literature, they originated in Indian epics by way of ancient drama/theatre. The epics and deities were our first films and actors, and much of the codes expressed (or not) in films are done in lieu of this old affinity. While some things have remained taboo (graphic violence, nudity, vulgar language), others have traveled across generations into the movie industry; e.g., elaborate costumes, fantasy, comedy, religiosity, and caste prejudice. These movies are filled with illogical, supernatural, and fantastic scenes because Indian storytelling tradition is rooted in the extraordinary. Unlike in the West, realism in India includes illusion (fantasy). Fantasy allows actors to oscillate across multiple locales and times, to imagine things not really occurring (e.g., a kiss), and, in general, makes a movie operate (as with life) on numerous levels simultaneously. While some of the comedy is downright ridiculous, the comedic usually occurs throughout the film including times of sorrow (unlike Hollywood). This juxtaposition of comedy and tragedy is no easy feat. For the West, comedy is primarily about humor; in the East, it is more sophisticated (and troubling); humor and gesture are involved. The extent of contortion of the contorted face sometimes outweighs the giggle it produces. As viewers, our problems are choice and education. Only a small percent of the commercial movies get to Guyana (emphasis is on the song/dance format). This makes us automatically ignore being analytical. What happens if the same Shabana Azmi of “Amar Akbar Anthony” is seen in a lesbian role (as in “Fire”)? Our entire perspective of the actress, her role, the movie, and our role as viewer is altered drastically. This civilized provocation is lacking in our cinema and living rooms. Thus, we need “parallel” or “independent” movies (non-commercially driven), to stimulate our concept of what movies are supposed to do, what we take from movies, and what to condemn. We need an education beyond film gossips (“Bollywood Buzz”) and “Star Dust.” Bollywood has improved over the years but it is far from substantial. Directors that challenge and break norms are refused distribution of their films and financial sponsorship. The caste roles depicted in Bollywood films are unlikable but necessary portraits of a society steeped in prejudice. Ironically, this representation allows the director (or art) to critique this fractured society. In many movies, certain prejudicial roles are challenged and resolved; the triumph of the hero, even in death, often means surmounting some type of social taboo. And while female roles suffer the most, sexism is, arguably, the most redressed role on screen; the mother/wife/lover usually finds redemption by the movies’ end, reversing patriarchal attitudes (e.g., “Kabhi Kushi Kabhi Gham”). Nevertheless, primary caste issues, in essence, are far from being debunked on screen. But Bollywood is no different from this world, which is sanctioned by histories of biased premises and sexist principles. Our “western” education was built on crooked philosophies. The flaws of our movie viewers are the vices of our movie culture, not India’s caste system primarily. For most, the “crude” of Hollywood, the true king of film filth, is style. If Indians demonstrate prejudices more than others, it is because they are subjected to double dose of racist movies and TV shows. If they do so because of caste attitudes passed down generations, we need social and religious education to arrest this, not the eclipsing of a movie type. And, if we are to remove an art form because of the nature of its content, then we must likewise renounce philosophy, literature, law, for all are prejudicial sciences. Because this is not possible, art education is needed to interpret the arts just as political education is necessary to make sense of political situations. Ash, jury member, at Cannes Film Festival 2003, France;and Shabana Azmi in Saaz. Unfortunately, since Guyana is a very narrow-minded society, “art education” may never occur among people who complain about long letters in newspapers. Today,we read and study less. We have more information/art, etc. at hand but want less to do with it. And, naturally, neither the politician nor educator sees the need for alternatives to our movie culture; thus, we are awarded the usual overload of political tales, from this “paper” or “thesis” to that “committee” or “conference.” Why? The same mundane, childish, outdated debates by essentially the same people have been occurring for the past 30 years. Intellectually, no one has grown up; artistically, we are dead souls. John Lennon (who meant more to me than Dr. Jagan or Burnham, when I was growing up in the 80s) once said the “trouble with the peace movement” was that there were a “lot of manifestos written by hawk-witted intellectuals and nobody’s reading them.” This is us. [Editor’s Note: Published in Stabroek News in June 2003 in response to claim by Dr. F. Kissoon that Bollywood movies are racist.] Page X>>> |

| June 23, 2003 |

©

2001 Guyanaundersiege.com |

Its

benefits are many of which its primary is its music. Plots are secondary.

In our estate communities, this music has sanctified Indian life;

the playback singers are companions and counselors in one. Where

public expression of intimate emotions is sparse, the song dissolves

inhibitions and social frustrations. Remove Indian movies and social

transgressors (depression, suicide) of the Indian community will

mount. However rich are Hindu weddings, they are impotent spectacles

without this music, which sets the tone and sustains the complex

event of rooted symbolism over days. Our “bottom house”

dancing is, in effect, reflective of the song-and-dance technique

employed in Hindi films,

Its

benefits are many of which its primary is its music. Plots are secondary.

In our estate communities, this music has sanctified Indian life;

the playback singers are companions and counselors in one. Where

public expression of intimate emotions is sparse, the song dissolves

inhibitions and social frustrations. Remove Indian movies and social

transgressors (depression, suicide) of the Indian community will

mount. However rich are Hindu weddings, they are impotent spectacles

without this music, which sets the tone and sustains the complex

event of rooted symbolism over days. Our “bottom house”

dancing is, in effect, reflective of the song-and-dance technique

employed in Hindi films,