| First of two interviews on GUS |

In more recent developments, the New York Film Institute hosted a week of selected films of Ms. Azmi in 2002 and in that same year, in October, she made a speech at the Asia Society titled "Coexistence and Conflict: Hindu Muslim Relations in India." Your first major role was in Shyam Benegal's Ankur ("The Seedling") in 1974, the film that essentially launched parallel or independent cinema in India. Do you think this role was important in determining the choices you have made since then? Completely. I think if I had not started with Ankur I would have landed up somewhere quite different. When I was still a student at the Film and Television Institute of India, I was selected by K. Abbas for his film Faasla. The first film that I actually started shooting the day after I graduated from the Film Institute was Kanti Lal Rathod's Parinay but then Ankur became the first film to get released and it was not only a big commercial success but also a very big critical success (it won me my first National Award). Like you said, Ankur became a very important film because it really launched parallel cinema in Hindi. Mrinal Sen had made Bhuvan Shome before that in 1969, but Ankur was really of critical important to independent film in India. The conditions under which you were raised were highly extraordinary. Your father was a prominent poet and member of the Progressive Writer's Association, the Indian People's Theatre Association, the Communist Party of India, and was involved in the anti-colonial movement. You have said elsewhere that this link between art and politicshas been ruptured in our times. Could you elaborate on that? Firstly, I would like to say that I grew up in a family that believed that art should be used as an instrument for social change. Both my parents practiced this principle: my father, through his work as an Urdu poet of great repute, as a film lyricist and also the scriptwriter of films like Garam Hawa, and my mother as a stage actress in India, who also worked with the Indian People's Theatre Association.

What ultimately drove me towards politics was this essential contradiction: if the whole purpose of art is to sensitize people, how can you say that this sensitivity is only going to be directed towards yourself and giving a better performance? This is simply not possible since the best resources of an actor must come from life itself. So when you are in films playing characters struggling with social injustice and exploitation, then a time comes when you can no longer treat your work like a nine-to-five job. I could not think that as of 6:00pm everyday, I would no longer concern myself with the lives of the people I choose to play. This turn came about some time in the early-80s. As far as the rupture between art and politics is concerned, I think it is really the choice of the filmmaker, which is fair enough because I don't believe it is right to claim that any one way of thinking is the best way; that I think is a fascist approach. I think people should have the freedom to make whatever it is they want to. I choose to use this medium as a vehicle for expressing my social concerns, which is not to say that I think everyone ought to do the same thing. You have frequently said this, that art is an instrument for social change. At the same time, you have argued that if any kind of social or political change is to occur, it will be through mainstream, not "parallel" cinema. Could you comment on this? Films have such a strong influence in India but when you try to bring about political or social change through art cinema, you are really preaching to the converted. In mainstream cinema, on the other hand, you have a much wider audience and a large number of issues to cover. When it comes to women, for instance, even the titles of earlier films like Main Chup Rahoongi suggest that keeping silent is a virtue for women. Women have largely been played in stereotypical roles, either as the suffering wife, or the forgiving mother, or the understanding sister. Until these stereotypical roles undergo some kind of progressive transformation in mainstream cinema, the message is not going to be communicated to the larger audience it ought to reach. I do think though that some kind of change is finally happening within mainstream cinema. People are now expecting women to be slightly more than bimbos; one can see that in the choices mainstream actors, like Karishma Kapoor or Madhuri Dixit, are making. These actors want to work in roles that give them substantially something to do; this is an indication of the fact that some kind of positive change is coming about in the mainstream.

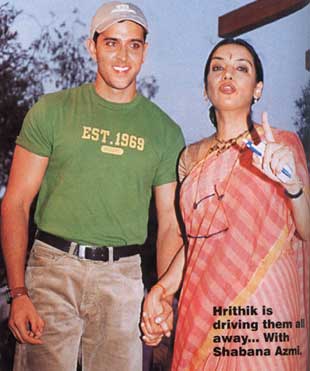

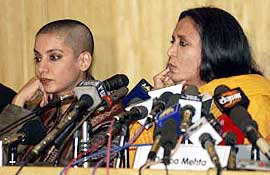

Shabana

with cropped hair and Director, Deepa Metha, Since the 1980s, however, that haschanged a lot, with the result that people have started expressing concerns about how heroines are now doing what only vamps did at one time. It is as though only a vamp can have an assertive sexuality; it becomes problematic when heroines express a similar sexuality. I don't think there is anything wrong with women celebrating their sexuality provided they are not at the same time surrendering to the male gaze. This is what happens frequently in mainstream cinema, and this is a problem because women are still allowing themselves to be commodified. The business of cinema is of course the business of images, so it is very easy for women to be used in this way. In that famous song, for instance, "Choli key peechay kya hai?" there were images of a heaving bosom, a swiveling hip, and so on, which catered entirely to the male gaze. This is a serious problem. So while I think there have been some advances on the issue of women's representation in mainstream cinema, there is still a long way to go. It is frequently argued that popular Indian cinema has, in the last decade in particular, become increasingly decadent. Do you think Indian film has changed dramatically in the recent past, and if so, to what do you attribute this change? Decadent, I think, is too strong a word. You must understand that the producer in mainstream Hindi cinema is interested in getting the largest number of people into his film so he is catering to the lowest common denominator. Mainstream Hindi cinema inhabits an alternative reality, which is based much more on fantasy; even a police inspector's house in an Indian film is nowhere close to what a police inspector's house looks like in real life. So it is this alternative reality that the Hindi film inhabits. However, these films still represent good values (evil doesn't pay, good does, and this kind of thing). I think the main problem is that not enough attention is paid to the script because there is this fear of creating real-life people. Simply because India is such a vast country, you feel that if the film is based in Gujarat, then people in the South will not identify with it, so you have what I call a "Miss Neeta" syndrome, where you don't give the character a surname, because a surname would immediately betray her origins; she would be localized and that would create problems. So the main problem is that not enough attention is being paid to the script. It is true as well that a particular kind of fantasy and opulence have come to dominate, about which I will speak in a minute. I think that there have also been a lot of technical advances; I think the Indian film industry is doing very well in that department (cinematography, etc.) There is a greater attention to what the film looks like but again, these visuals are also divorced from reality because they are not operating with reality, they inhabit and portray an alternative reality. One of the main problems as far as what you call decadence is concerned -- and this is a recent phenomenon -- has to do with filmmakers increasingly catering to an NRI audience. This NRI audience seems to be more interested in a modern, more westernized look, but the values that these films propagate (ostensibly for this audience) are completely traditional and almost retrograde. What direction do you think Indian cinema is going in now? Frankly I am not upset with the state of affairs of Indian cinema; I know a lot of my colleagues are. A lot of people are very fond of saying that parallel cinema is completely dead which I don't agree with at all. I feel that a different kind of parallel cinema is being attempted by people like Dev Benegal, Sudhir Mishra, Kaisad Gustad, Mira Nair, Deepa Mehta. All of these people are talking about their own reality, which is an urban, contemporary, English-speaking reality. These films are now also being made in English because these directors are looking for an international market (not to mention of course that this is also a very important part of India). It is not as though parallel cinema can, or should, only speak about peasants being exploited by the feudal classes. India is a country that lives in several centuries simultaneously; there are people living back to back from the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries and her people encapsulate all the contradictions that emerge from this. I am very tired of the view the West seems to have of India: a Third World country, exotic-despite-famine-and-drought, spirituality as its essence, etc. I think India is a very vital, dynamic country, full of contradictions, and these are being brought out and discussed in contemporary parallel cinema. If you want that to be projected, it is not going to come from the West; it has to come from filmmakers in India who are projecting what is their reality and are also a part of the national fabric of India. So I don't think parallel cinema is on the wane at all.

As far as mainstream cinema is concerned, it is carrying on. Because a lot of big-budget films have not succeeded I think the film industry is having a problem. The advent of a film like Dil Chahta Hai directed by Farhan [Akhtar] is very very important because it addresses an urban reality, and talks about the rich, but not in an exploitative way, and still manages to convey the director's reality. The film wasn't a huge success but at least it got very good reviews and the revenues more than covered its costs. So this is encouraging for directors like Farhan who can now go on to make other films like that. Lagaan was also a huge success and Lagaan is a mainstream film I really enjoyed very, very much. In another interview, you recall telling your father, renowned poet, Kaifi Azmi, that his poetry had become reduced to a medium for his political beliefs so it was no longer "art". Do you feel that art is sullied by politics, or made less pure by any contact with it, that it is compromised by such proximity, that there is in fact something like art for art's sake? I am a professionally trained actor, so that is what my discipline was. I was trained with the Stanislavski method, and was told that for an actor, it is important to be able to play any part at all. A good actor should be able to prefix the words, "If I were…" to any one of a range of characters (a prostitute, Mother Teresa, Queen Elizabeth) and be able to play each equally well. For me, however, that is no longer possible because of my political beliefs. I think, of course, that art for art's sake does exist, but that is simply not a choice that I can make any longer because I have very strong political beliefs. When I asked this of my father, I was genuinely interested in hearing what his perspective on this was. But the minute I asked the question, my mother said, "Well, look who's talking. Look at what's happening to you." In fact it was very interesting, because Aparna Sen, who's a filmmaker who I respect a great deal but also a very close friend of mine, said that my off-the-screen image has become so strong now that she would hesitate to cast me in certain kinds of roles. Because even if she were to cast me as a woman who has been victimized she would already have revealed the story because if I were in the story it would mean that I would eventually escape the victimization. This is not good for an actor because an actor should not really have such a strong personality outside the part that she is portraying. That is a struggle within me. For instance, I would never do a film which endorsed the idea that women are subservient and should remain so. That is such an obvious choice that I wouldn't have a struggle with that. I had a real struggle with the film Godmother because I found it a very interesting and unusually complex part within the mainstream. I spent a long time deciding whether I should take the part or not. The women's movement has always claimed that we need to get more women into the political arena to change the nature of politics and yet Godmother showed a woman who to a great extent surrendered to the system and became corrupt. But then the director explained to me that the part cannot be viewed through this prism alone. He explained that he himself did not view the film that way but rather as a story about how communities can be mobilized and manipulated by vote-bank politics. When seen through this prism, the film resonates in a completely different way. So it was a struggle for me because while I was really attracted by the part, I also firmly believe that women need to change the very nature of politics. I have been part of the movement that has said that we need 33 per cent reservations for women because I strongly believe that when women come on to the political scene, they will change politics itself. This change then can only come about if a critical mass of people are converted to this way of thinking. Otherwise the world is not going to be a better place; it's only when you transform the very notion of power so that it becomes about sharing, rather than about the powerful wielding power over the weak. So there were a number of things I thought of, and I felt confused initially, but ultimately I am very happy I did the part in Godmother.

Well, it was a process, it did not happen with any one such thing. I would date it to perhaps my role in Mahesh Bhatt's Arth. The film is about a woman who is abandoned by her husband for a girlfriend. The wife is completely devastated by this but eventually gets herself together and becomes her own person. At some point, the husband returns and asks for forgiveness saying he made a mistake. The wife responds by asking whether he would have taken her back if she had made the same mistake, and the husband says he would not have. So she chooses to walk out on him. When we were screening the film for possible distributors, everyone said it was a wonderful film but it would not run a day unless we changed the end because an Indian woman rejecting her husband after he has apologized is completely unacceptable. Mahesh Bhatt and I dug our heels in and said that this was precisely why we were making this film and we were going to stick with the ending. It came as a huge surprise to us that the film became a very big success. Apart from winning me the National Award, it also became in a sense a cult film. Suddenly I had women walk into my house expecting me to resolve all their marital problems. They were no longer reacting to me as fans to a star, but as a sister, as a woman. I was overwhelmed and I was really scared because I had not really given it a moment's thought and then I realized that in fact I am being put in a position of great responsibility. With Arth I started getting invited to seminars and becoming involved in activism of that kind. This was happening on the one hand. On the other hand, I was working with Goutam Ghosh in Paar and we were living in this small little shantytown in Naihati. How I work usually is to try and find in real life somebody who is similar to the part that I'm playing. I found this slum-dweller who I was using as a role model to observe the way she walks, the way she talks, the way she eats, etc. and in the process we became friends. A couple of days into the shooting, she took me to her house and I was so completely shocked when I saw how poor that little tenement was. There was no water, no electricity, no air, and I was completely amazed that somebody who was living in such torturous circumstances had the generosity to become my friend. I felt that if I went back and didn't attempt to bring about any change in the lives of people like her, it would be a travesty of the trust she had placed in me when we became "friends." It would be like saying, "I will use you and win a National Award in the bargain, but I won't concern myself with your life at all." It became really very difficult for me to do that. Then I came back to Bombay and saw a film by Anand Patwardhan called Bombay Our City, which really brings into focus the fact that demolition is not the solution to slums. Demolition only creates worse slums out of already existing slums. Some slums that are demolished have water and electricity; the slums that replace them frequently do not. People also do not go back to the village if their housing is destroyed because they have come to the city in search of work. If they had work in the village they would not come to the city. Instead they move 5 km away to another slum, which may not even have water or electricity; a worse slum is thus created. Then I got involved with a group called Nivara Hakk (which means the right to shelter), which works for slum-dwellers in Bombay. In 1986 we went on a hunger strike after a big slum was demolished and the government was not giving its former tenants any alternative land, which they were entitled to under the policy. It was a five-day hunger strike, and ultimately we forced the government to give them the land. Why did you decide to run for parliament? What has the experience of being a parliamentarian been like? What kinds of opportunities and constraints has this presented? I was nominated for parliament by the President of India in 1997, I did not run. I am not an elected member of parliament, I am a nominated member. For the past several elections, people had been asking me to contest elections and I had always resisted that because I don't think I am meant for party politics. Party politics is really about putting the fetters on because the party's truth becomes your truth and you have to tow the line, which I never wanted to do. But when I got this opportunity, I realized that it was an opportunity to bring the voice of the grassroots to the place where issues are discussed. What it has given me is the opportunity to influence debates on housing and on women's rights by bringing the voice of the activist and of grassroot-workers to the place where legislation is framed.

I still think it is a very important opportunity and I enjoy it. I think parliament is much derided and people say nothing happens and everyone screams and shouts. But that is not what parliament is about; you really need to do a lot of homework before you can get up and actually speak. The business of parliament is to form legislation and in order to do that, the kind of scrutiny that a bill undergoes is quite remarkable and the public never gets to see that.

|

| November 28, 2003 |

©

2001 Guyanaundersiege.com |

PRELUDE

on Shabana Azmi—

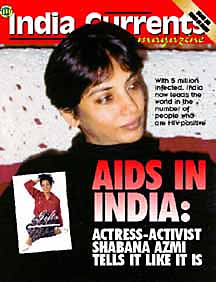

Shabana Azmi is an internationally acclaimed actress, Member of

the Indian Parliament, and UN Goodwill Ambassador. She is the

winner of an unprecedented five National Awards for Best Actress

in India for the films Ankur (1974), Arth (1983), Khandhar (1984),

Paar (1985), and Godmother (1999) and international awards for

best actress at the Taormina Arte Festival in Italy for Patang

(1994), the Chicago International Film Festival and the Los Angeles

Outfest for Deepa Mehta’s Fire (1996). Several retrospectives

of her films have been screened at the George Pompidou Center

in Paris, the Norwegian Film Institute, the Smithsonian Institute

and the American Film Institute in Washington as well as at the

Pacific Cinemetheque and Winnipeg Cinematheque. She has been chairperson

of the jury at the Montreal International Film Festival and the

Cairo International Film Festival. She won international acclaim

in John Schlesinger’s Madame Sousatzka, co-starring Shirley

Maclaine, Nicholas Klotz’s The Bengali Night co-starring

John Hurt and Hugh Grant; and Roland Joffe’s City of Joy,

co-starring Patrick Swayze. Other films include Channel 4’s

Immaculate Conception, opposite James Wilby in The Son of Pink

Panther by Blake Edward and Isma il Merchant’s In Custody.

Shabana Azmi, wife of poet, lyricist, and screenwriter Javed Akhter

and daughter of renowned Urdu poet, Kaifi Azmi, and seasoned stage

actress, Shaukat Kaifi, is a graduate in Psychology from St. Xavier

College in Mumbai, India. She secured her diploma in acting from

the Film and Television Institute in Pune, India. Also as chairperson

of the Nivara Hakk Suraksha Samiti she arranged for alternate

land for the disputed slum dwellers of Sanjay Gandhi Nagar in

Mumbai and undertook to diffuse tensions after the demolition

of the Babri Masjid. For her excellence in social activism, Shabana

Azmi won the Rajiv Gandhi Award as well the Yash Bhartiya award

from the government of the state of Uttar Pradesh, India. Most

significantly she was awarded the Padma Shri in 1988 by the Government

of India. This is an award given to eminent citizens for excellence

in their field and distinguished contribution to society. The

President of India has also nominated Shabana Azmi as Member of

Parliament of upper house or Rajya Sabha. Azmi has recently been

appointed as United Nations Goodwill Ambassador on Population

and Development.

PRELUDE

on Shabana Azmi—

Shabana Azmi is an internationally acclaimed actress, Member of

the Indian Parliament, and UN Goodwill Ambassador. She is the

winner of an unprecedented five National Awards for Best Actress

in India for the films Ankur (1974), Arth (1983), Khandhar (1984),

Paar (1985), and Godmother (1999) and international awards for

best actress at the Taormina Arte Festival in Italy for Patang

(1994), the Chicago International Film Festival and the Los Angeles

Outfest for Deepa Mehta’s Fire (1996). Several retrospectives

of her films have been screened at the George Pompidou Center

in Paris, the Norwegian Film Institute, the Smithsonian Institute

and the American Film Institute in Washington as well as at the

Pacific Cinemetheque and Winnipeg Cinematheque. She has been chairperson

of the jury at the Montreal International Film Festival and the

Cairo International Film Festival. She won international acclaim

in John Schlesinger’s Madame Sousatzka, co-starring Shirley

Maclaine, Nicholas Klotz’s The Bengali Night co-starring

John Hurt and Hugh Grant; and Roland Joffe’s City of Joy,

co-starring Patrick Swayze. Other films include Channel 4’s

Immaculate Conception, opposite James Wilby in The Son of Pink

Panther by Blake Edward and Isma il Merchant’s In Custody.

Shabana Azmi, wife of poet, lyricist, and screenwriter Javed Akhter

and daughter of renowned Urdu poet, Kaifi Azmi, and seasoned stage

actress, Shaukat Kaifi, is a graduate in Psychology from St. Xavier

College in Mumbai, India. She secured her diploma in acting from

the Film and Television Institute in Pune, India. Also as chairperson

of the Nivara Hakk Suraksha Samiti she arranged for alternate

land for the disputed slum dwellers of Sanjay Gandhi Nagar in

Mumbai and undertook to diffuse tensions after the demolition

of the Babri Masjid. For her excellence in social activism, Shabana

Azmi won the Rajiv Gandhi Award as well the Yash Bhartiya award

from the government of the state of Uttar Pradesh, India. Most

significantly she was awarded the Padma Shri in 1988 by the Government

of India. This is an award given to eminent citizens for excellence

in their field and distinguished contribution to society. The

President of India has also nominated Shabana Azmi as Member of

Parliament of upper house or Rajya Sabha. Azmi has recently been

appointed as United Nations Goodwill Ambassador on Population

and Development. For

quite some time I did not really involve myself in politics. When

I first started films, I felt I had already had too much politics

at home so I wanted to stay away from it. Inevitably, though,

the soil was so fertile that the plant had to take root.

For

quite some time I did not really involve myself in politics. When

I first started films, I felt I had already had too much politics

at home so I wanted to stay away from it. Inevitably, though,

the soil was so fertile that the plant had to take root.  If

you look at the way women have been projected in Hindi cinema,

in particular, you will see two or three strains. On the one hand,

the very strong mother, who is typically a clone of mother India.

Then there is the vamp who, interestingly, was always someone

with blue eyes and blond hair (which can be attributed, I think,

to our colonial hangover and the implication that only such women

could legitimately be the objects of sexual desire). And lastly

of course there was the heroine. What is interesting though is

that there was always a very clear division between the vamp and

the heroine.

If

you look at the way women have been projected in Hindi cinema,

in particular, you will see two or three strains. On the one hand,

the very strong mother, who is typically a clone of mother India.

Then there is the vamp who, interestingly, was always someone

with blue eyes and blond hair (which can be attributed, I think,

to our colonial hangover and the implication that only such women

could legitimately be the objects of sexual desire). And lastly

of course there was the heroine. What is interesting though is

that there was always a very clear division between the vamp and

the heroine.  I

think the problem still remains with distribution; these films

have a tough time getting into theatres. I have been telling the

government for a long time that if they want to promote independent

cinema, they should get out of the business of producing films.

They should focus instead on the distribution network. More private

producers will produce these films if they are ensured distribution.

So there are different problems with parallel cinema but it has

certainly not disappeared.

I

think the problem still remains with distribution; these films

have a tough time getting into theatres. I have been telling the

government for a long time that if they want to promote independent

cinema, they should get out of the business of producing films.

They should focus instead on the distribution network. More private

producers will produce these films if they are ensured distribution.

So there are different problems with parallel cinema but it has

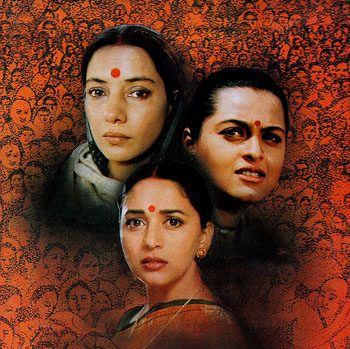

certainly not disappeared.  (Left,

Shabana in Mrityudand, also starring Madhuri Dixit.)

(Left,

Shabana in Mrityudand, also starring Madhuri Dixit.) In

terms of actual performance, I think my strength and my weakness

is the same. My strength is that I have an independent voice,

and my weakness is that I don't have a party to back me. So there

is only this much that I can do; I can bring about a certain concern

to the debate but ultimately because I don't have a party backing

me, I haven't managed to change all that much - that perhaps is

being too modest!

In

terms of actual performance, I think my strength and my weakness

is the same. My strength is that I have an independent voice,

and my weakness is that I don't have a party to back me. So there

is only this much that I can do; I can bring about a certain concern

to the debate but ultimately because I don't have a party backing

me, I haven't managed to change all that much - that perhaps is

being too modest!