THE burly British film crew gazes in wonder at

the image of the stunning young Indian woman on the playback monitor.

As her jeweled sari radiates ruby and amber across their faces,

the woman smiles out at her audience, stifles a giggle and draws

butterfly-wing lashes down over olive-green eyes. A pause, she

looks up, throws her head back and laughs, then withdraws into

another coy smile. The shot, five bewitching seconds that may

not even make the final edit of Bride and Prejudice, ends. The

crew doesn't move. Without a word, the tape is rewound and another

viewing begins. It is perhaps the seventh or eighth in a row.

"Marvelous," sighs an assistant director. His fellow

crew members nod in vigorous agreement. Behind them producer Deepak

Nayar beams at director Gurinder Chadha. "After this,"

chuckles Chadha, "she'll be able to do anything she wants."

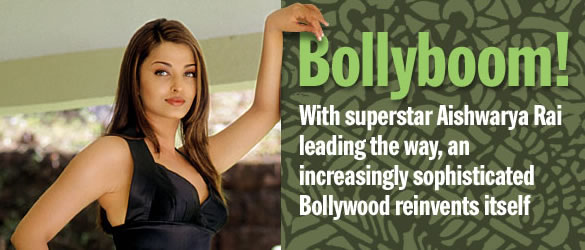

Aishwarya ("Ash") Rai has been a superstar in India

since she was crowned Miss World in 1994, so seducing a film crew,

even her first British one, doesn't faze her. "It's not just

about how I look," she says in the elegantly articulated

English of the Indian élite. Indeed, after a handful of

forgettable movies in the 1990s, Rai earned gushing reviews for

her performances in last year's Devdas, for which she won seven

Indian critic awards, and this fall's Chokher Bali. In Devdas

in particular, critics swooned over her transformation from innocent

lover to jilted avenger and agreed that she more than held her

own against Bollywood's biggest male star, Shahrukh Khan, and

Bombay's other queen, Madhuri Dixit. But Rai's looks—"the

most beautiful woman in the world," according to Julia Roberts—haven't

hurt her, either.

Rai turned Western heads this spring as a Cannes festival jury

member and the new face of cosmetics house L'Oreal. The attention

led to her invitation to the airy hills north of London, where

she is now playing the lead in Bride and Prejudice, Chadha's hotly

anticipated follow-up to her hit movie Bend it Like Beckham. Bride

is a modern, Bollywood version of Jane Austen's classic, in which

the Bennetts of Pemberley become the all-singing, all-dancing

Bakshis of Amritsar. But Rai's soaring star doesn't rely on one

film alone. Scarcely does she wrap Bride before rehearsals start

for The Rising, an epic based on the failed 1857 Indian rebellion

against British rule. Then, in March 2004, her agents confide

with considerable glee, the 29-year-old ex-model is slated to

start shooting opposite Meryl Streep in Chaos, French director

Coline Serreau's remake of her acclaimed drama about a housewife

who adopts a battered prostitute, a role that will mark a daring

departure for Rai. If that weren't enough to guarantee her arrival,

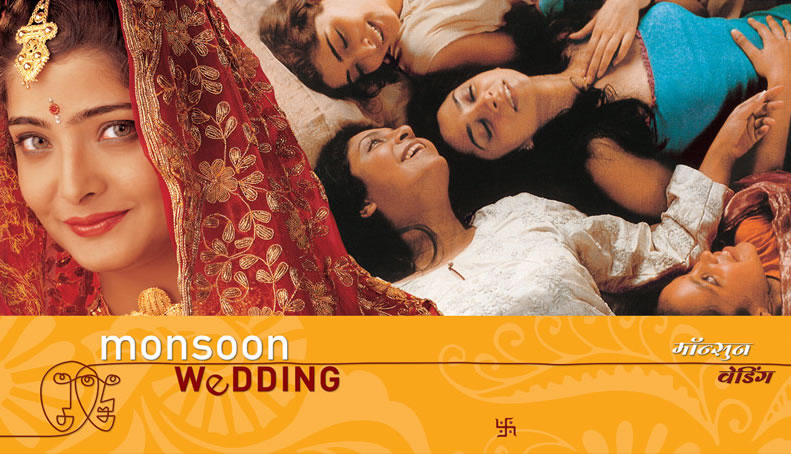

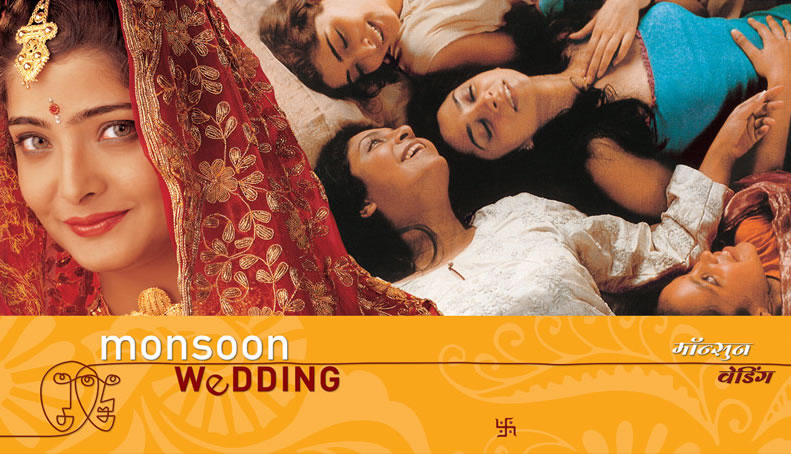

Rai is also talking to director Mira Nair (Mississippi Masala,

Monsoon Wedding) about a part in Homebody/Kabul, based on Tony

Kushner's play about the Taliban. And she's signed up to star

in India's first IMAX production, Taj Mahal. All five movies should

release worldwide over the next 18 months, by which time, Nair

predicts, Rai "will be the next Penelope Cruz."

But Cruz never brought along an entourage like

this. For although 2004 may be Rai's year, it is shaping up as

Bollywood's breakthrough, too. Following Rai westward will be

India's brightest male star, Aamir Khan, whose Lagaan (Land Tax)

was nominated for an Oscar in 2001 and who returns opposite Rai

in The Rising. Western audiences will also be introduced to Indian

art-house icon Rahul Bose, who will appear with Glenn Close in

Merchant Ivory's Heights, a contemporary tale of five affluent

New Yorkers. And behind the camera this trickle of A-list Indian

talent becomes a monsoon flood. In addition to its British-Indian

director, Bride and Prejudice combines the skills of legendary

Bollywood choreographer Saroj Khan and sought-after Bombay cinematographer

Santosh Sivan.

Meanwhile, director Shekhar Kapur (Elizabeth, Bandit Queen) has

announced a return to India with a $25 million production called

Paani (Water), set in 2060 Bombay but slated for a worldwide release.

Fellow auteur Vidhu Vinod Chopra is currently casting the thriller

Move 5 in Los Angeles. And Ugandan-Indian Nair will be unmissable

in 2004. She releases Vanity Fair, starring Reese Witherspoon;

takes Monsoon Wedding to Broadway; starts work with Rai on Homebody/Kabul;

directs a star-studded adaptation of British writer Hari Kunzru's

The Impressionist, and executive produces three Indian films under

a deal with Universal Studios worth up to $15 million. (Caption:

Ash in Bride and Prejudice, a take on Jane Austen's Pride and

Prejudice.)

Meanwhile, director Shekhar Kapur (Elizabeth, Bandit Queen) has

announced a return to India with a $25 million production called

Paani (Water), set in 2060 Bombay but slated for a worldwide release.

Fellow auteur Vidhu Vinod Chopra is currently casting the thriller

Move 5 in Los Angeles. And Ugandan-Indian Nair will be unmissable

in 2004. She releases Vanity Fair, starring Reese Witherspoon;

takes Monsoon Wedding to Broadway; starts work with Rai on Homebody/Kabul;

directs a star-studded adaptation of British writer Hari Kunzru's

The Impressionist, and executive produces three Indian films under

a deal with Universal Studios worth up to $15 million. (Caption:

Ash in Bride and Prejudice, a take on Jane Austen's Pride and

Prejudice.)

Nor is the traffic one way. Following 20th Century Fox's decision

to pick up The Rising, the first Indian-made movie that a Hollywood

studio will release worldwide, Warner Bros. and Columbia TriStar

Films are both planning to distribute Bollywood films abroad.

Going a step further, a handful of Western independents are inaugurating

a rash of East-West coproductions using Bombay's cheap, skilled

workforce. Shooting recently started on The King of Bollywood,

with British supermodel Sophie Dahl; and winter should see production

begin on Marigold, a story of an American B-movie actress stranded

in India.

It will all give a distinctly Indian flavor

to some of next year's biggest movies. And to their makers, stirring

in a little spice makes perfect sense. Chadha says her theft of

Austen will work because Bollywood shares themes with Western

art of a more innocent age. "When you see how perfectly the

plot of Pride and Prejudice fits Bollywood, you see how Austen

and Bollywood use the same language of joy, love, family and sadness

that's so uplifting and involving, and so rare and different from

Hollywood today," she says. "I think the audience will

eat it up." For Nair, the explanation is even simpler. "The

West is suddenly waking up, noticing what the rest of the world

has been watching all these years and working out where it came

from." She predicts more international exposure for Bollywood

as Hollywood realizes the commercial sense of combining the world's

two biggest film audiences.

Already, on the set of Vanity Fair, Bollywood's leap onto the

global stage has afforded her some deliciously surreal moments:

playing up Calcutta-born William Thackeray's Eastern influences

with a dance sequence, she says, "I had all these white folks,

these big stars, lined up, doing my thing, dancing to my Indian

tunes." Nair guffaws: "It was wonderful!"

The

film world has heard rumors of an Indian invasion for years. In

London in particular, the success of cross-cultural writers like

Vikram Seth, Hari Kunzru and Monica Ali, Andrew Lloyd Webber's

Bombay Dreams, department store Selfridges' decision to adopt

a Bollywood theme, and a host of wildly successful Indian TV comedies

has long convinced the British public that it was set for a Bollywood

bonanza. Often, the sheer size of the Indian film industry—releasing

an average 1,000 films a year, compared with Hollywood's 740;

and attracting an annual world audience, from Kuala Lumpur to

Cape Town, of 3.6 billion, compared with Hollywood's 2.6 billion—made

it seem as though the West was the last to catch on. But even

though Chinese film boomed with Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon,

somehow the Indian wave never broke. And although Indian films

showed in theaters from Singapore to San Francisco, the truth

was that few Asians, Europeans or Americans outside the vast South

Asian immigrant community actually saw them.

The

film world has heard rumors of an Indian invasion for years. In

London in particular, the success of cross-cultural writers like

Vikram Seth, Hari Kunzru and Monica Ali, Andrew Lloyd Webber's

Bombay Dreams, department store Selfridges' decision to adopt

a Bollywood theme, and a host of wildly successful Indian TV comedies

has long convinced the British public that it was set for a Bollywood

bonanza. Often, the sheer size of the Indian film industry—releasing

an average 1,000 films a year, compared with Hollywood's 740;

and attracting an annual world audience, from Kuala Lumpur to

Cape Town, of 3.6 billion, compared with Hollywood's 2.6 billion—made

it seem as though the West was the last to catch on. But even

though Chinese film boomed with Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon,

somehow the Indian wave never broke. And although Indian films

showed in theaters from Singapore to San Francisco, the truth

was that few Asians, Europeans or Americans outside the vast South

Asian immigrant community actually saw them.

Ash arrives as

jury member at the 2003

Cannes Film Festival, France.

The reason was not hard to fathom. However deep the artistic void

that gave the world Death Wish V or Police Academy 7, Bollywood

has long outdone Hollywood for formula and cliché. After

a two-decade-long golden age that produced films such as Mother

India (1957) and Sholay (1975), the industry slipped into a succession

of hackneyed action flicks and copycat song-and-dance romances

made under a factory ethic in which actors worked on five, 10,

even 15 films at a time. Remakes and plagiaries of Hollywood were

routine, scripts were almost unheard of, and cast and crew often

took the same characters, shots and dance steps from one production

to another. The love stories were particularly indistinct: thousands

of boys met thousands of girls (songs of joy!), broke up (songs

of sorrow!), reunited (joy!) and led a cast of hundreds to a meadow

outside Zurich for a leaping, ululating and face-achingly joyous

finale. Actors sleepwalked through careers. "You can't imagine

what it was like," says Anupam Kher, star of 290 films in

18 years, who reprises his role as the father from Bend it Like

Beckham in Bride and Prejudice. "After the whole fame thing

wears off, you begin to wonder, 'Really, what the hell am I doing?'"

Even domestic audiences complained, including India's leader.

"Why do our films stick to stereotype?" lamented Prime

Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee after seeing Devdas, which for all

its well-deserved critical praise, was still the 12th version

of the same love story since the original 1928 silent movie. By

mid-2002, Bollywood was largely a commercial concern—to

this day, critics rate films and actors almost entirely by box-office

pull—of little interest to anyone outside South Asia, except

homesick migrants and the odd film buff.

So what's changed? Everything. Rai's unchallenged position in

the industry is partly due to her determined pursuit of "different,

against the grain" roles, such as her 1997 part in Tamil

director Mani Rathnam's little-seen but acclaimed art-house movie

Iruvar. But Rai is not some solitary crusader, rather the most

successful disciple of a new mantra of innovation that has swept

Indian film in the past year. Because in 2002 Bollywood truly

bombed. All but 12 of the year's 132 mainstream Hindi releases

flopped, and the $1.3 billion-a-year industry, used to comfortable

annual growth of 15%, groaned under unaccustomed losses of some

$60 million. The formulas suddenly weren't commercial anymore.

And although some moviemakers groped around for new blueprints—horror,

skin flicks, anything—a band of urban and Westernized writers,

directors, producers and actors, loosely grouped under the banner

"New Bollywood," overran the industry. "Overnight,

those of us who didn't think the audience was dumb and who were

sick of movies being talked about as 'products' were in charge,"

says producer-of-the-moment Pritish Nandy. "The old generation

lost control, and the new generation just walked in."

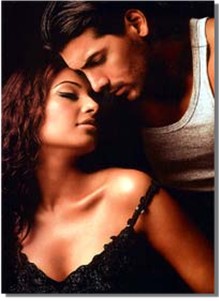

(Left,

Bipasha Basu and John Abraham in Jism.)

(Left,

Bipasha Basu and John Abraham in Jism.)

Today, fresh ground is broken with every release. Out are fluffy

romances. In are films such as Jism (Body) [ Note, Mumbai Matinee

and Khwahish (Desire) that have shattered Bollywood's tradition

of prudish sex scenes, by making previously taboo kisses routine

and by finally ditching the rustling bushes that used to denote

what came next. Out are badly dubbed punchups and in are dark

stories like the true tale of Bombay's rival crime lords (Company)

or India's Hindu-Muslim divide (Mr. and Mrs. Iyer), weird stories

like that of a hairdresser who reads minds (Everybody Says I'm

Fine) or a retired judge who literally runs off with a young model

(Jogger's Park) or dark and weird tales like the one of a failed

rock singer who leads his bandmates to murder (Paanch). Urban,

middle-class films like Dil Chahta Hai (Do Your Thing) are proving

there is money in ignoring India's rural audiences, whose preferences

run to the spectacular, the musical and, invariably, the alpine.

Some films are even leaving out the songs. Director Ram Gopal

Varma dropped the music from both Company and his smash horror-thriller

Bhoot (Ghost). "It doesn't make sense to a Western audience,"

Varma explains over drinks at Bombay's Hyatt Hotel. "I live

in this country, and I've still not got used to it. And, frankly,

I couldn't give a f--- for the villages." (During the conversation,

Varma took a revealing call from a film distributor in Dubai.

He cheerfully informed the caller, "There is no music in

the film, only background music. You won't really hear it."

He then turned to a TIME reporter, grinning, with his hand over

his phone, and laughed, "'No songs! No songs!' He's having

a heart attack." After hanging up, he added: "I'm in

that position now, you know? 'F--- you! Take it or get out!'")

If music is used today, it's for a reason. Bride

and Prejudice choreographer Saroj Khan, 55, says that for 600

films she did nothing but "item numbers," dance sequences

inserted with little regard for narrative. "Now suddenly

I have a story to work with," she says. "You won't believe

me, but that's very different. And very nice." Concludes

Kaizad Gustad, director of Boom (about three supermodels who must

somehow find the money to pay for 30 Mob-owned diamonds they've

lost): "Suddenly, the newer and riskier the project, the

greater the chance of it getting made."

Propelled by this whirlwind of raw creativity, star after star

is breaking type and embracing new roles, recharging some long-languishing

talents. Like Rai, Bombay legend Amitabh Bachchan is trying something

different, raising eyebrows with his portrayal of the stylishly

amoral, Bo Derek-obsessed crime kingpin in Boom. "It's a

crazy film by a crazy guy," offers the 61-year-old with evident

delight while on the set of his new war movie Lakshya (Target).

And producer Nandy cheerfully expects a torrent of outrage upon

release of the gritty Chameli, as megastar Kareena Kapoor dumps

her customary chaste refinement to play the streetwalker of the

film's title opposite Rahul Bose's banker. The head of 20th Century

Fox's Indian arm, Aditya Shastri, describes the industry as suddenly,

and fundamentally, transformed. "It takes a very brave or

very foolish person to do a traditional song-and-dance movie today,"

he says. Bose, who as the star of Chameli, Mr. and Mrs. Iyer,

Mumbai Matinee and Everybody Says I'm Fine is the ubiquitous face

of New Bollywood, goes further: "Put us all together, and

you have a movement. Put us together with the audience, and you

have something sweeping the world."

On the set of Bride and Prejudice, Rai is already coping with

some of the pitfalls of the revolution. After every scene, she

quietly slips past the longing stares of 100 Indian extras and

retreats to her cordoned-off trailer. This past year she has already

endured her own "Bennifer" style press attention when

she split from fellow movie star Salman Khan only to link up with

the star of Company, Vivek Oberoi. The size of her celebrity is

measured by the 17,000 unofficial websites in her name and the

immediate overloading and crash of her own official site the moment

it was launched this spring. Ensconced in her trailer, she admits

to having "so little time to myself and for my sanity. Last

summer, I had meetings with Robert De Niro and Roland Joffé

and Mike Leigh," she says. "They'd say, 'When are you

available?' And I'm like, 'Maybe at the end of next year.' And

they're like, 'Wow, you can't be serious.' But that's my life

right now."

Indeed, Rai seems to have little time even to sleep: she scheduled

both her photo shoots with TIME for the middle of the night, saying

it was her only free time, before crying off exhausted on the

second shoot and finding a spare two hours the following day.

But you won't hear Rai complain. "I can always choose to

do something else," she shrugs. And she seems to accept that

as a model turned actress with no training, she's on a steep,

and tiring, learning curve. "I'm a student," she says,

hands folded neatly in front of her. "I want to do better,

and I want directors who can find the actress in me and be my

teachers." But like many of Bombay's bigger stars, one of

her first lessons was to turn herself into something of a recluse,

never discussing her private life and rarely being photographed

in public. "I like my work, and I'm true to it; and apart

from that, I'm just being," she says.

Mira

Nair (with Reese Witherspoon on the set of the upcoming Vanity

Fair) is everywhere in 2004: Along with Vanity Fair, Nair

is

working

on two star-studded literary adaptations and a Broadway production

of her hit Monsoon Wedding. Note poster at

right.

In between. In between, she's executive-producing on a three-picture

deal with Universal Studios worth $15 million.

Overwhelmed by the demands on their time or simply by their own

importance, lead actors in Bollywood would in the past jeopardize

entire productions by double-booking themselves, turning up hours

late on set (sometimes not appearing at all) or raising fees midway

through a shoot. But bigger names, such as Rai and Bose, are now

signing with Western talent agencies (both are with the gilt-edged

William Morris Agency) that ensure commitments are honored. Amitabh

Bachchan, who for years set a lonely example of professionalism

in Bollywood, couldn't be happier. "It's a joy to be working

like this," he says. "To end the disorganization that

has ruled for so long, it's an absolute delight."

It's all part of a newfound professionalism in Bollywood that

is evident both artistically and financially. On the set of Lakshya,

at Film City studios outside Bombay, this new regimen is in full

effect. Director Farhan Akhtar and producers UTV have fixed a

budget of $7 million (large by Bollywood standards), issued contracts

to crew and actors, insisted on a finished script, insured the

set and laid out a meticulously detailed schedule for months of

continuous shooting in Bombay and Ladakh. Such black-and-white

commitments may be rudimentary in the West but are almost unprecedented

in an industry in which a quiet word or a handshake have long

sealed deals and in which films were shot piecemeal over a number

of years.

Likewise, the financing of Bollywood movies has become far less

murky. In the 1990s, a series of scandals broke about the links

between Bombay's movie world and the underworld. Producers were

the target of repeated police investigations into how deeply Mob

money had penetrated the movies, and top actors who were called

to testify often sensationally refused. Indeed, just last month,

Devdas producer Bharat ("King of Bollywood") Shah was

sentenced to a year in jail (but released due to time served)

for concealing the underworld's involvement in his 2000 movie

Chori Chori, Chupke Chupke (On the Quiet, Hush Hush). In the past,

such attachment to Mob money and the conditions that came with

it—flying stars to Dubai, Pakistan or South Africa to indulge

gangsters' egos—proved a major deterrent to Western investors.

But today, even Bombay's police admit the connection with the

underworld is weakening—a transformation that began in October

2000, when India's bureaucrats finally lifted outdated restrictions

on Bollywood's access to banks and private investors. As legitimate

funds poured in from respectable backers, so a new culture of

legal and transparent business practices swept the industry.

New Bollywood is not there yet. Director Nair estimates that it

will be "two or three years" before its movies attain

what she calls Western-style "craft and rigor," and

UTV's founder, Ronnie Screwvala, adds that it will take "three

to five years" before Western business practices become standard.

In the meantime, maybe the greatest danger of Bollywood's invasion

of the West is that the West might invade right back. Director

Varma's urbanized zeal for Hollywood—"anyone who doesn't

follow the West is gone"—carries with it the danger

that, in less-skilled hands, Indian film could become little more

than exotic imitation. Although he admits to enjoying how well

the world received Lagaan and although he welcomes New Bollywood's

energy, actor Aamir Khan warns that a wholesale rejection of song

and dance might kill the "color, fire and innocence"

that defines Indian cinema. "Of course, Bollywood can be

quite ghastly," he says. "But at its best, it's a wonderful

form. There's a level of passion and excitement and a heightening

of emotions which can be momentous. It'd be awful to lose it."

With Rai as India's standard bearer, there is

little immediate danger of that. She may position herself as New

Bollywood in terms of roles, but in person Rai embodies the Indian

middle-class—and very Old Bollywood—ideal: a modern

girl with traditional values. For someone emerging as a 21st century

film star, there are few people less likely to turn into a Western-style

sex kitten. Asked about her image as every Indian man's dream

girl, she replied: "I'm just being the girl I was brought

up to be." In fact, it is because Rai is such a paragon of

age-old, dutiful Indian femininity, says producer Nayar, that

she was so right for the headstrong but obedient Elizabeth Bennett

character, Lalita. "That's her appeal," says Bride and

Prejudice co-star Martin Henderson. "When Hollywood women

are so exposed—when you see ass cheeks hanging out on MTV,

for God's sake—there's something wonderful about a woman

who is sensible and refined, mysterious and sensual."

In an age of terror, perhaps it makes sense for audiences to yearn

for a more innocent time. Rai agrees that although New Bollywood

may represent a welcome reinvigoration of a tired industry, the

reason she is suddenly attracting a global audience is the same

reason that Bollywood has always drawn adulation from millions

of Indians. "It's the chance to be transported from the toil

and the worry," she says, "the chance to feel good about

life again." Whatever the innovations of the new Indian wave,

the true essence of Bollywood, she says, will always be "a

world of hope and color and positivity, the innocent, beautiful

fairy tale." So is this the beginning of a storybook adventure

for her and Indian cinema? Why not? As she says, "In Bollywood,

it's always a happy ending."

[Editor's Note: All credits to

TIME ASIA except title herein, the captions, the Rai photo at

Cannes, and the poster for Monsoon Wedding. The first photo as

been edited.]

Meanwhile, director Shekhar Kapur (Elizabeth, Bandit Queen) has

announced a return to India with a $25 million production called

Paani (Water), set in 2060 Bombay but slated for a worldwide release.

Fellow auteur Vidhu Vinod Chopra is currently casting the thriller

Move 5 in Los Angeles. And Ugandan-Indian Nair will be unmissable

in 2004. She releases Vanity Fair, starring Reese Witherspoon;

takes Monsoon Wedding to Broadway; starts work with Rai on Homebody/Kabul;

directs a star-studded adaptation of British writer Hari Kunzru's

The Impressionist, and executive produces three Indian films under

a deal with Universal Studios worth up to $15 million. (Caption:

Ash in Bride and Prejudice, a take on Jane Austen's Pride and

Prejudice.)

Meanwhile, director Shekhar Kapur (Elizabeth, Bandit Queen) has

announced a return to India with a $25 million production called

Paani (Water), set in 2060 Bombay but slated for a worldwide release.

Fellow auteur Vidhu Vinod Chopra is currently casting the thriller

Move 5 in Los Angeles. And Ugandan-Indian Nair will be unmissable

in 2004. She releases Vanity Fair, starring Reese Witherspoon;

takes Monsoon Wedding to Broadway; starts work with Rai on Homebody/Kabul;

directs a star-studded adaptation of British writer Hari Kunzru's

The Impressionist, and executive produces three Indian films under

a deal with Universal Studios worth up to $15 million. (Caption:

Ash in Bride and Prejudice, a take on Jane Austen's Pride and

Prejudice.) The

film world has heard rumors of an Indian invasion for years. In

London in particular, the success of cross-cultural writers like

Vikram Seth, Hari Kunzru and Monica Ali, Andrew Lloyd Webber's

Bombay Dreams, department store Selfridges' decision to adopt

a Bollywood theme, and a host of wildly successful Indian TV comedies

has long convinced the British public that it was set for a Bollywood

bonanza. Often, the sheer size of the Indian film industry—releasing

an average 1,000 films a year, compared with Hollywood's 740;

and attracting an annual world audience, from Kuala Lumpur to

Cape Town, of 3.6 billion, compared with Hollywood's 2.6 billion—made

it seem as though the West was the last to catch on. But even

though Chinese film boomed with Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon,

somehow the Indian wave never broke. And although Indian films

showed in theaters from Singapore to San Francisco, the truth

was that few Asians, Europeans or Americans outside the vast South

Asian immigrant community actually saw them.

The

film world has heard rumors of an Indian invasion for years. In

London in particular, the success of cross-cultural writers like

Vikram Seth, Hari Kunzru and Monica Ali, Andrew Lloyd Webber's

Bombay Dreams, department store Selfridges' decision to adopt

a Bollywood theme, and a host of wildly successful Indian TV comedies

has long convinced the British public that it was set for a Bollywood

bonanza. Often, the sheer size of the Indian film industry—releasing

an average 1,000 films a year, compared with Hollywood's 740;

and attracting an annual world audience, from Kuala Lumpur to

Cape Town, of 3.6 billion, compared with Hollywood's 2.6 billion—made

it seem as though the West was the last to catch on. But even

though Chinese film boomed with Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon,

somehow the Indian wave never broke. And although Indian films

showed in theaters from Singapore to San Francisco, the truth

was that few Asians, Europeans or Americans outside the vast South

Asian immigrant community actually saw them.  (Left,

Bipasha Basu and John Abraham in Jism.)

(Left,

Bipasha Basu and John Abraham in Jism.)